Christian Perrone, Fellow, Datasphere Initiative

This blog provides an overview of the Brazilian proposals on e-evidence and cross-border data for investigation purposes. Based on the concept of the Datasphere — defined as the “complex system encompassing all types of data and their dynamic interactions with human groups and norms”¹ I explore how a new normative and procedural “toolbox” for e-evidence could allow flexibility for data to responsibly flow internationally with respect for the interoperability of different legal systems. Through this blog, I demonstrate how such an effort could help balance the interests of law enforcement with the imperatives of human rights.

The cross-border nature of data and particularly e-evidence

Over the past 30 years, the internet has changed the way crimes are committed and more so how they are investigated. Crimes committed online and also committed offline leave electronic traces (i.e. “e-evidence”), as individuals use electronic means or, at the very least, plan their actions online. Thus, access to such evidence has become a key concern for Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) across the world.

The borderless nature of the internet results in this e-evidence potentially being processed and connected to multiple countries. This creates a layer of complexity for identification and responsible (legal, ethical, and human rights driven) access. For example, a crime may have been committed in one country, through the actions of a person that may or may not be a national of the same country, with a residency potentially in another, and the data itself may be in possession of a foreign company, which potentially stores data in a server located in yet a different country from where it is headquartered. Hence, requests for access to e-evidence regularly involve cross-border efforts. Such initiatives tend to be dependent on: (i) defining jurisdiction over the data; (ii) having available legal instruments to request access to the e-evidence (even if it may have a cross-border impact); and (iii) protecting the rights of all parties involved (including the rights of the accused party).

Countries have yet to agree on all three elements — jurisdiction over data, the availability of legal instruments, and the protection of rights of all parties involved. Current judicial cooperation regimes — such as the Mutual Legal Assistance system (MLA system) — are considered in need of reform to respond to exigencies of time and expediency.

Internationally, the OECD (see more here), the UN, the Council of Europe, among others have developed initiatives to facilitate and provide responsible and safe mechanisms for these requests of access with cross-border connections. All have faced several obstacles in terms of international agreements around them.

In the absence of an overarching international legal mechanism, many countries (and regions) propose and develop their own unilateral initiatives. Brazil seems to be a significant laboratory of all such discussions as the country can provide illustrative examples of both what can go right — or wrong — through the adoption of domestic unilateral solutions.

The quest for a domestic instrument

From the standpoint of Brazil, large amounts of e-evidence tend to be in the possession of multinational companies, chiefly “Big Tech”, which generally store and process data overseas. This means that even parochial cases where crimes were committed in Brazil, allegedly by nationals, with Brazilian victims, may have cross-border implications.

The legal discussion, hence, refers to the obligations of internet service providers to comply with domestic requests of e-evidence. Central to it is the question of whether the fact that the data is located overseas establishes the necessity to follow an international cooperation mechanism (particularly using a Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty, “MLAT”) or whether it would be possible to request information “domestically” (under a solely “national” procedure). The debate reached the Brazilian Supreme Court (“Supremo Tribunal Federal”) under the guise of whether the US-Brazil MLAT is constitutional (ADC nº 51, “Ação Direta de Constitucionalidade nº 51”).

While providing a way to access data, the MLA System tends to be considered too cumbersome and time-consuming — taking an average of 12 to 18 months to have a result (average proposed by the Brazilian Government, in the US, a report states the average is 12 months).

In terms of domestic procedures, several LEAs and the Brazilian Ministry of Justice have argued that article 11 of the Brazilian Internet Bill of Rights (“Marco Civil da Internet”) would provide legal authority to directly request access to data in possession of internet service providers (ISPs).

In Brazil, there is no specific clear domestic unilateral procedure that addresses the cross-border issues raised by the Brazilian LEAs. Additionally, no specific mechanisms to deal with jurisdictional conflicts (e.g. a blocking status) exist to support handing over data directly to foreign authorities.

This means that if there is a direct judicial request to an ISP outside the MLAT, the request won’t come accompanied with clear guarantees and safeguards for individual rights impacted.

Legislative proposals

There are several other initiatives that discuss a domestic unilateral solution, in some ways they follow the footsteps of the US CLOUD Act, which also put an end to a constitutional dispute over access to data stored overseas.

In Brazil, the one proposal that received the most attention is the inclusion of an article in the so-called “Fake News Bill” (Draft Bill 2630/2020). Additionally, a reform of the Criminal Procedure Code is under discussion in Brazil. One of the proposals aims at providing express legal authority for judges to request access to data directly from ISPs, notwithstanding the location where data is stored or processed.

One should note that in both cases several of the safeguards and guarantees being discussed elsewhere are not present in the Brazilian domestic debate. The cross-border dimension appears to be absent as well, particularly in terms of the rights of the data subject — especially if they are foreigners — and in terms of potential jurisdictional conflicts. Thus, these legislative initiatives, granted, will establish a specific domestic procedure yet they do not address much of the underlying challenges of cross-border direct requests of data. For that, a new approach — a toolbox — is necessary.

Towards a Datasphere approach: designing an e-evidence toolbox

The example of Brazil showcases both the quest for a solution and the potential pitfalls as unilateral procedures without an underlying mental model may lead to less protection and more jurisdictional conflicts.

The concept of a Datasphere — as a “complex system encompassing all types of data and their dynamic interactions with human groups and norms” — provides an opportunity to reimagine data governance on a global scale. The focus shifts from a discussion of jurisdiction over data, to how data can flow internationally responsibly and with accountability.

Introducing a three-part toolbox

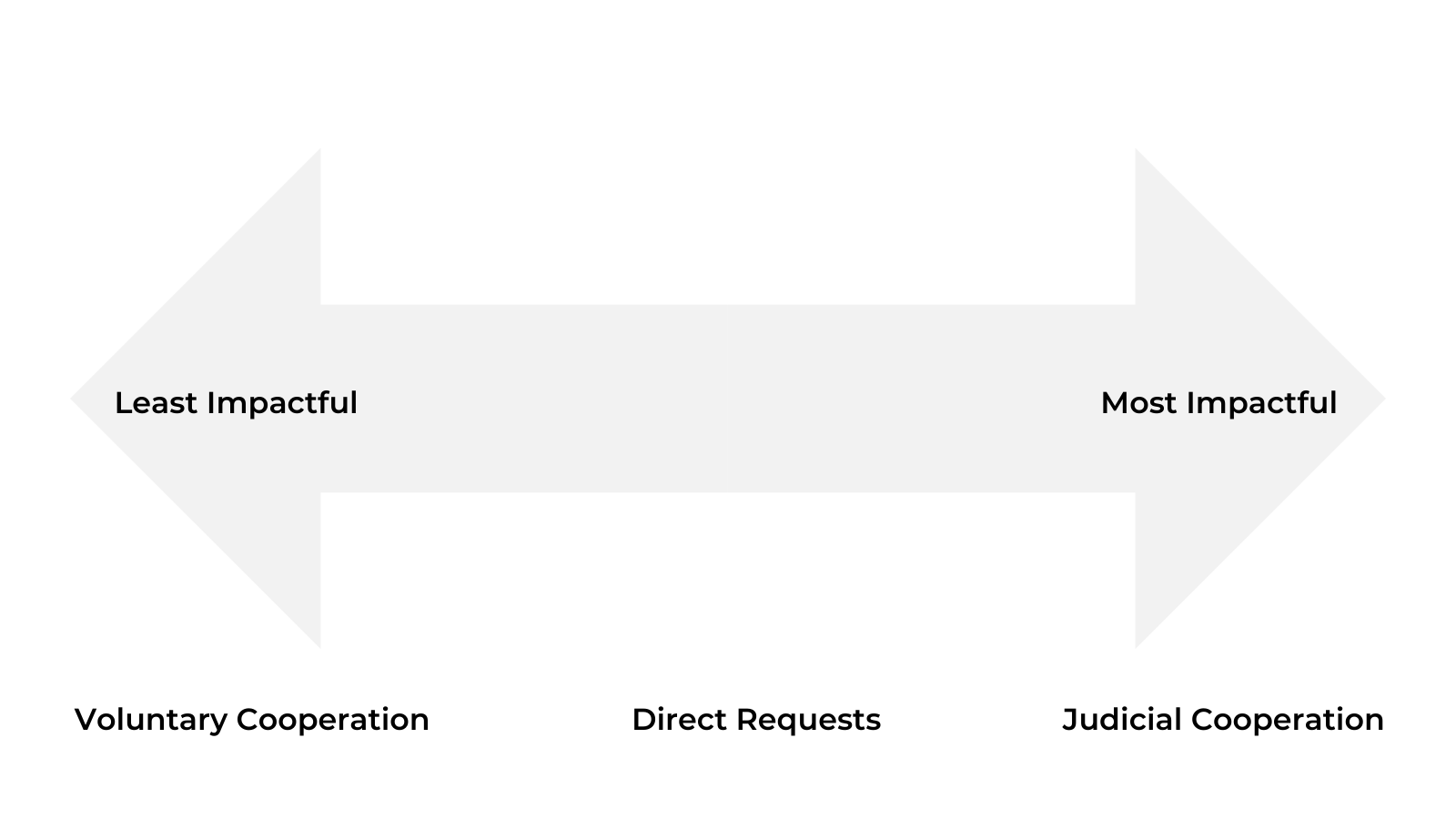

It is clear that not all countries will regulate LEAs’ access to rights the same way and will strike different balances between competing human rights (such as privacy, fair trial, victims’ rights, etc.). Yet, if we look at this issue through the context of the Datasphere, we can re-conceptualize LEA request for access to e-evidence in terms of interoperable legal systems. This could potentially mean understanding different mechanisms of access to data as a three-part toolbox with voluntary cooperation, direct requests, and judicial cooperation is available on a scale from the least to the most impactful to human rights and other jurisdictions.

Key elements of this approach could take the form of the below:

Voluntary cooperation by ISPs may be available in situations where LEA can indicate the necessity of such data for an investigation and the risk to an individual’s rights is lower. One example is subscriber data from a national LEA country.

Direct requests, on the other hand, may depend on satisfying a higher threshold (eg. showing probable cause) and having in place significant safeguards including. In such procedures, there may be a need to establish a substantial connection with the forum and the legitimacy of the request.

Finally, a judicial test may be relevant for deciding whether this type of request is available.

Conclusion

The MLA system or other international cooperation regimes may need to evolve in order to better reflect the needs of our times and the constantly evolving and fast-moving inter-relationships we have with data. E-evidence is one example that demonstrates a need for clarity and up-to-date international arrangements to avoid what has already been called “a legal arms race”. New policy procedures or “toolboxes” that take inspiration from the interoperable nature of the concept of the “Datasphere” could help frame the complex issues affecting stakeholder rights and the ability to deal with harms and the flow of data.

¹De La Chapelle, B. and L. Porciuncula (2021), “Hello Datasphere”, Datasphere Initiative Medium, https://medium.com/@thedatasphere/hello-datasphere-towards-a-systems-approach-to-data-governance-d602f96c9e1d