Christian Perrone, Fellow, Datasphere Initiative

As the story goes, after the storm, the mighty and strong oak, torn up, questions how the feeble and flexible reeds were still standing. Aesop’s fable of the oak and the reeds seems to indicate that the choice between flexibility and rigidity might have far reaching consequences and sometimes be surprising.

Here is the challenge the Brazilian data protection authority faces in regulating international data transfers – the core focus of my Fellowship with the Datasphere Initiative this past year. Many of the examples of regulations of international data transfers seem to fit in a scale of flexibility and rigidity – with the European Union in the most rigid side, Singapore in the most flexible and New Zealand seemingly somewhere in the middle.

Brazil, then, appears to be in the position to learn from the different options and choose its own path, but what should it be? This blog post intends to explore this dilemma and we propose that the concept of the Datasphere – “the complex system encompassing all types of data and their dynamic interactions with human groups and norms” – may suggest a new framework to look at how to regulate international data transfers based on a broader and holistic data governance strategy.

Understanding the Brazilian Dilemma

The Brazilian Data Protection Regulation (“LGPD”) articles 34 and 35 mandate the data protection authority (“ANPD”) to regulate international data transfers. The legislation follows much the same structure of the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) as it proposes that there may be decisions on countries that are considered adequate for data transfers, and to all others, there would be available mechanisms for data transfers such as standard contractual clauses or model contractual clauses (“SCCs” or “MCCs” or “CPCs” in the Portuguese acronym for “cláusulas padrao contratuais”).

On May 18, the ANPD started a multistakeholder consultation process on how it should regulate international data transfers. The public consultation seemed to emphasize particularly the contractual mechanisms, chiefly the aforementioned SCCs. However, early on, the public debate showcased a lack of consensus on the regulatory path the ANPD should take on the matter. Some favor a path similar to the EU based on a very structured a priori prescription of how the contractual clauses should be, while others argued for more flexible approaches as those adopted by Singapore (agents can choose from a multitude of SCCs that Singapore or any other country provide) or New Zealand (where core clauses and complementary clauses come together to allow for the needs of the business), as later explained.

The arguments expressed within the Brazilian consultation, and towards one or another model, seem to take into consideration four different elements: (i) the recent constitutionalization of the right to data protection (see a commentary about it here); (ii) the Brazilian socioeconomic context1, considering as well the incipient data protection culture of the country; (iii) the global position of Brazil in the data processing value chains (most as consumer of services), not to mention the complexities of such chains; and (iv) the costs of implementing the different approaches both for the economic sector (transaction costs) as for the administration (fiscalization costs). Stakeholders could not agree on the combination of the four that should better suit the Brazilian data protection ecosystem and, while securing rights, would promote local innovation and international cooperation.

Understanding the Available Regulatory Models

The European model – The prescriptive

The European regulation – both the directive 95/46 and the EU GDPR, – creates a system where cross-border data transfers are dependent on having in place legal, technical and administrative mechanisms that provide a certain level of data protection, particularly in terms of the rights of data subjects. These mechanisms may vary according to circumstances from the country where data is being exported to. If the place is considered adequate as per the decision from the European Commission, then the transfer can occur; otherwise, it is necessary for the parties interested in the transfer to put in place additional arrangements, such as adopting “Standard Contractual Clauses”2 or SCCs.

In terms of SCCs, the EU decided for a prescriptive view where the data supervisory authorities had to publish beforehand the clauses and they had to be implemented in totum by controllers and processors whenever they exported data across borders. Very recently, new SCCs have been approved that provide for more options of SCCs which actors can choose from.

The benefits of such approach seem to be particularly the facilitation of the negotiation and consequent diminishing of transaction costs, the previsibility of obligations and results and the facility within which authorities can oversee compliance. One should note, however, that the same easiness of oversight does not translate to verifying the practice adopted by controllers and processors when implementing the clauses through their operational and company-level data management approaches.

Two challenges, however, derive from this approach:

- it may limit the number of actors in the data processing value chain that may be included in a particular negotiation, as standard contractual clauses may not encompass certain positions in the data cycle – for instance, sub-processors in a different country -, admittedly the new EU clauses provide more options such as for subcontractors; and

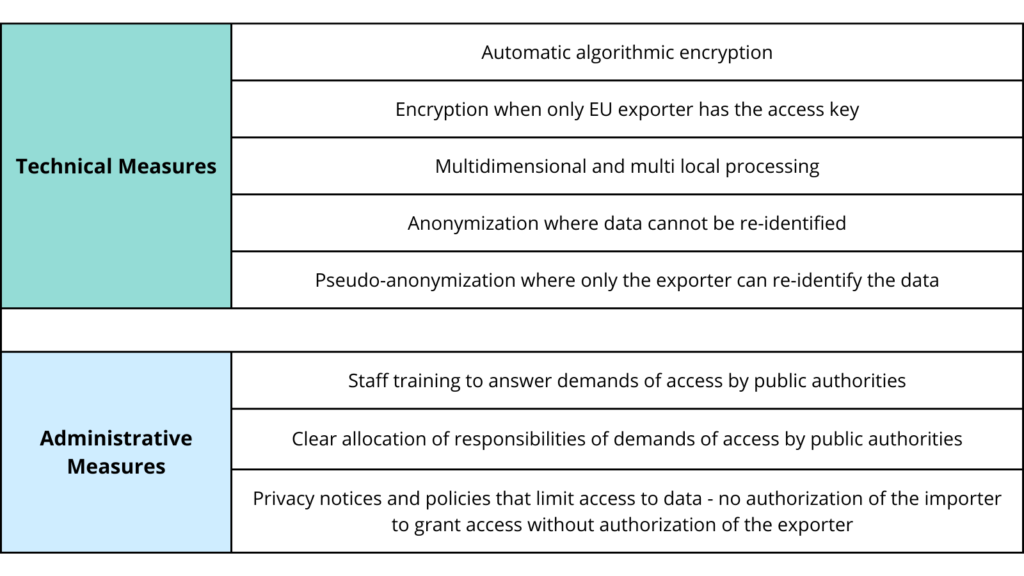

- based on the certain implications3 of considerations around the recent decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union –CJEU’s decisions, particularly the Schrems II case, ), a deeper evaluation of the legal ecosystem and business practices adopted in the country importing the data might consequent additional specific clauses and practices (See table below) as suggested by the European Data Protection Body (“EDPB”) and the European Data Protection Supervisory (“EDPS”) be necessary. However, this latter challenge impacts the benefit of reducing transaction costs that homogeneous and general SCCs (the “one model fits” all approach) generate.

The potential consequence of these two implementation challenges is a de facto localization of data in the EU, especially for organizations and businesses with fewer resources to deal with the complexity.

The Singapore Model – The contrast

Singapore, which is on the other side of the spectrum, has a much more flexible approach. Instead of predetermined sets of clauses, there are model clauses that agents can choose from and may adapt to their particular needs. This model also allows actors to actually choose from other countries SCCs, such as the standard European clauses and other jurisdictions´s regulations. Thus, this modularity approach potentially allows for more choice and adequacy. The core of the protection rests in the data protection principles that have to be obeyed together with the rights of the data subjects.

This approach has the advantage of facilitating adjusting contracts to the global data cycles and value chain complexities, and perhaps facilitating legal interoperability since actors can choose to adopt the SCCs of one relevant market – beyond Singapore – across all its contracts with all the markets they operate with. Its disadvantages, however, are that it depends on a higher understanding of data protection and may lead to negotiating costs, not to mention in complexities for the oversight of the Singaporean data authority that has to check whether the core tenets of protection are present.4

New Zealand´s Model – The middle ground

New Zealand’s approach has been a blend of a core prescriptive approach, where certain core standard contractual clauses should be present, while providing certain clauses that can be adapted to the reality of the data cycle and the agents position in the business value chain.

As advantages, this model presents two: First, it tends to provide more previsibility and facilitate negotiations as the language of most clauses is already prescribed. Second, it is possible to adjust some of its language to satisfy specificities in terms of the exact processing that is going to happen and the actor prepared to work on it. As for challenges, as some parts may be adapted, the risk for data subjects rights might still be present and both the negotiating costs and complexity for fiscalizing compliance are still high.

Words of Caution for Stakeholders as they consider data transfer pathways

Two additional dimensions may be considered as well, when stakeholders and the Brazilian ANDP are considering the model forward. First, not all countries and regions are the same and are in the same position to negotiate internationally, as for instance the EU (more about that see Brussels Effect). Countries’ different political clout, internal markets or overall attractiveness may impact the decision of controllers and processors to operate in a certain space. Thus, a more rigid or a more flexible approach can open up or restrict (for the better or for the worst) services’ available for one place or the other.5

Moreover, a high standard of protection that may limit international flows may lead to “indirect data localization”6, with its own set of complexities. Not to mention that, as noted by Prof. Anupam Chander, this “localization logic” may not necessarily prevent foreign governments from requesting access to data from companies in a certain territory even if data is in servers located in the country of origin of the data. Thus, the potential loophole that the restriction of international data transfers aims to fill may still exist, no matter the effort to localize data.7

The Datasphere and a possible new approach

The objective of regulating international data transfers in general is that personal data collected from citizens and residents of one country or region is processed under standards at minimum compatible with the ones nationally imposed and that data subjects rights are respected despite the cross-border transfer – data subjects´ expectations of privacy and protection should, then, be safeguarded.

As noted by the Advocate General (AG) Saugmandsgaard Øe “in the absence of common personal data protection safeguards at global level, cross-border flows of such data entail a risk of a breach in continuity of the level of protection guaranteed in the European Union”. Thus, in his view it is necessary to implement mechanisms for the creation of the proverbial “bubble of protection” enveloping the data and to safeguard against it being “burst”, or circumvented.8

The concept of the Datasphere provides a more holistic approach that can, even through the unilateral lenses of national regulation, showcase the interconnection of data flows that enables the Datasphere we live in. If one looks at the phenomenon of international data flows being regulated, one understands that no regulatory action happens in a vacuum The consequences of each regulatory path reverberates in the whole system. It may even incentivize responses from the different actors, public or private. The net result of the regulatory effort should be understood according to the multitude of repercussions that may even be in detriment of the one regulating.

Thus, under a concept of the Datasphere, the regulatory avenue tends towards convergence and mechanisms of legal interoperability. Certain aspects such as mutual recognition, standard agreements and rules favoring the rights of the data subject seem all to represent the trend a concept of a Datasphere may showcase.

The Brazilian data protection authority may apply the very same logic of a Datasphere concept in order to analyze the best course of action. Hence, favoring an approach that is in accordance with the position of the country in relation to the Datasphere.

¹Despite having high levels of internet usage per capita, Brazil does not have significant global internet companies, yet has a growing startup environment that may lead the way.

²The EU Commission also developed Questions and Answers (Q&As) to provide practical guidance on the use of the SCCs and assist stakeholders in their compliance efforts under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/questions_answers_on_sccs_en.pdf

³After the decision, different data protection authorities understood that without strong supplementary measures, data could not be exported to the United States, thus several services based in the US, from cloud computing to analytics, could be impacted. The supplementary measures pushed forward in guidance from the European Data Protection Body (“EDPB”) and European Data Protection Supervisory (“EDPS”) focus mostly on anonymization and encryption of data. Such specific additional measures tend to be costly and mostly either insufficient or limiting the value of the data transferred. Hence, controllers and processors will likely avoid transferring the data overseas and de facto localizing data.

⁴One should note that SCCs from other jurisdictions may already be pre-approved, thus facilitating the process.

⁵There are many other potential consequences, particularly for countries with less “market power”. The ones mentioned here serve as examples of such impacts.

⁶Even if data localization is not mandatory, companies will tend towards having data stored locally so as not to run the risks and costs of international transfers.

⁷In order to understand the logic of limiting access, particularly from the standpoint of the European Union, see for instance: Vogelezang, Francesco. The Data Act: five implications for the Datasphere. Datasphere Initiative blog: https://medium.com/@thedatasphere/the-data-act-five-implications-for-the-datasphere-d6529ef9c255

⁸The European Commission noted that the “protection travels with the data no matter where the data is”, thus demanding the creation of a “bubble of protection”. (European Commission, ‘A European strategy for data’ (19 February 2020), p. 23).