Brian Tshuma, Fellow at the Datasphere Initiative

Introduction

Chan (2013) has aptly reminded us that there are more and other ways than the mainstream to imagine the relation between technology and people (Hintz et al., 2022).

Thus, as part of my fellowship at the Datasphere Initiative, I plan to explore non-mainstream principles, institutions, and interventions that can be developed to support data governance frameworks that better account for the specificities of Sub-Saharan Africa. This first blog post provides initial impressions on the data policy landscape to ground this research.

Today’s paradigm of Big Data treats data like property to be acquired – the large number of mergers and acquisitions in the platform sector point to that trend clearly. But if we accept this as the mainstream, we might only enrich corporations and governments and endanger everyone else.

Indeed, several alternatives, contending different imaginaries have emerged in relation to ratification. Concepts like “datasphere” (Porciuncula and Chapelle, 2022), “data worlds”, (Gray, 2020) “data frontiers” (Beer, 2017), or “data futures” (Ruppert, 2018) emphasize the capacity of citizens to perform and imagine data differently.

They underscore how citizens ‘reorient datafication in ways that unfold new horizons of significations’ (Hintz et al., 2022). The idea of data imaginaries, a subfield of social imaginaries, refers to “the capacity of a given society to create new meanings within which it is able to think itself.” “[D]ata imaginar[ies] can be understood to be part of how people imagine data and its existence, as well as how it is imagined to fit with norms, expectations, social processes, transformations, and ordering.” Inextricably related to practice and action, data imaginaries are sprouting into different directions across the world as I write, complementing, rivaling, or contesting the Big Data narrative.

Current Trends in the African Continent

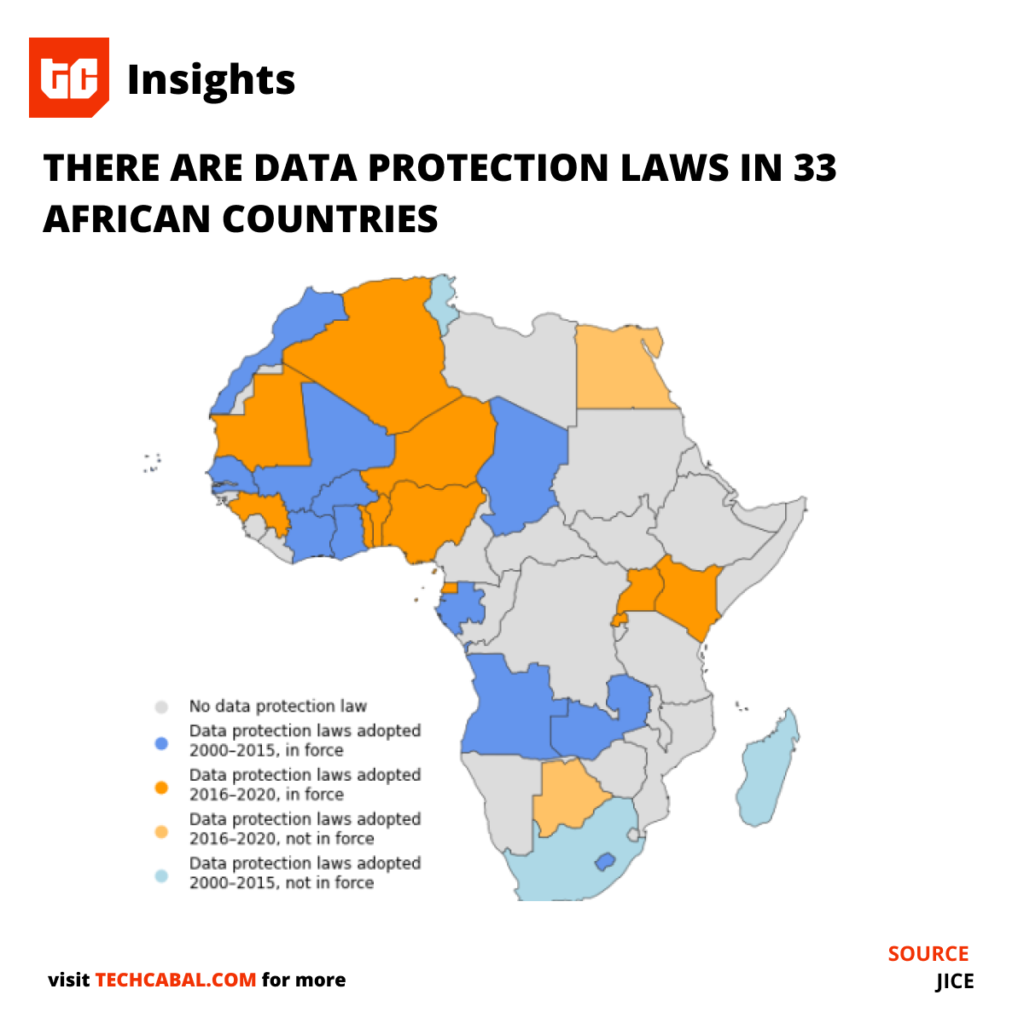

Africa’s reliance on Brussels (that is, the European Union or EU) for policy instruments to enact relations between technology and its people cannot be denied. In the frenzied race to adopt EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), privacy and data protection are elevated to the status of, and used as a synonym for, data governance. The one-size-fit-all GDPR imaginary, as reflected in key instruments like the AU-Africa Data Policy Framework (African Union, 2022), Regional Model Data Protection Laws, or the Malabo Convention (African Union, 2014), is criticized for ‘foregrounding human agency as individual market choice, where personal data serves the interests of individuals.’

Figure 2.1. The African race (in full throttle) to adopt the GDPR Model Laws for Data Protection, adopted from TechCabal newsletter. (Source: Daigle, 2021)

While African countries are celebrating the speed with which the continent is catching up on adoption of GDPR-like norms, Brussels has moved forward and recognizing the complexity of data governance, is pushing forward, under the EU Data Strategy two additional norms further enacting the Data Act (European Commission, 2022) and Digital Services Act (The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2022) for example, to provide for broader developmental goals.

Beyond the adoption of foreign norms, one can also observe the push for the adoption of foreign governance structures, such as trusts. While collaborative approaches are welcomed, African countries have a long history of community pooling and management of resources within local cities, villages, and tribes. Examples include arrangements known as ‘igombana laBashe,’ ‘Zhunde ra Mambo’ or Isiphala seNkosi’ (Ndlovu, 2021) in Southern Africa.

Thus, African countries should also look into what is next needed in terms of data governance regulatory development. In this regard, we adopt the following definition of data governance: “Data governance concerns the rules, processes, and behaviors related to the collection, management, analysis, use, sharing, and disposal of data – personal and/or non-personal. Good data governance should both promote benefits and minimize harms at each stage of relevant data cycles.”

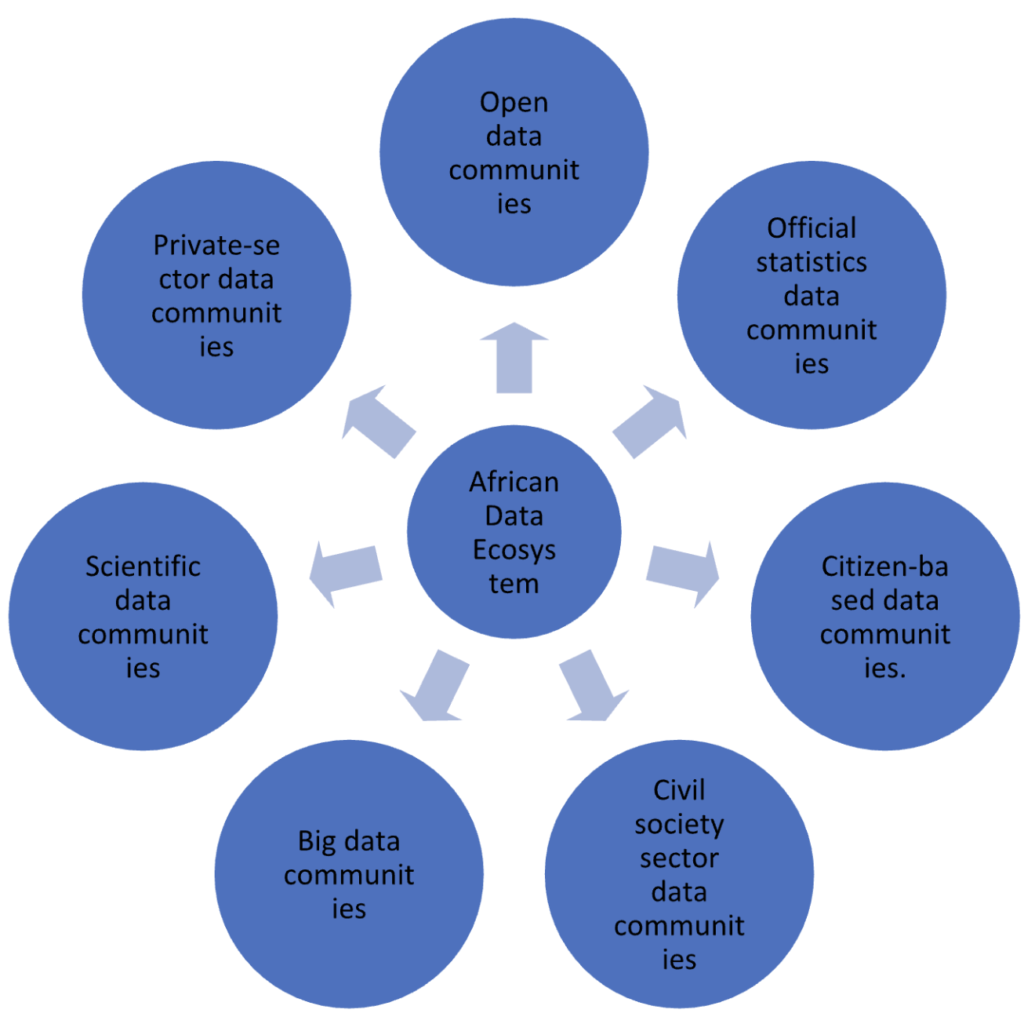

As many, the African data landscape is a complex one, where various actors contribute to its formation via different behaviors, datasets, and management approaches, with various elements forming it, as shown in the picture below. To think about an adequate data governance system that responds to local needs, that complexity needs to be understood.

Figure 2.2. The one-size fit all GDPR regime of data protection does not sufficiently provide for risks and challenges faced by multiple data communities in the African datasphere (Source: self-compiled).

Advocating for an African approach

Thus, and as advocated by organizations such as the Datasphere Initiative and Aapti Institute in India for instance, there is a need to understand the complex system that frames local needs – such as those deriving from political, cultural, social justice – in order to develop adequate data governance frameworks and institutions that work locally. Such a move would ensure that African traditional value systems such as Ubuntu, Umoja, Kujichagulia, Ujima, Nia, Kuumba, or Imani (Karenga, 2017), are accounted for in governance of data.

Additionally, we should not disregard innovative governance structures that are being adopted across the world for better, more open, and transparent governance and decision-making, such as citizen assemblies, citizen councils, citizen juries, citizen summits, distributed dialogues, or citizen panels.

Rehashing colonialism and casting data as a raw material (“data as oil”), the open exploitation of which must be curtailed by African leaders through sovereignty or localisation, just as was done with coal, gold, platinum, or other mineral resources is inadequate.

African people’s ethos of interconnectedness derived from Ubuntu, Umoja, Kujichagulia, Ujima, Nia, Kuumba, or Imani, suggests an all-encompassing data imaginary, which views data as a public good which belongs to the people and takes data agency as civic agency, would align better with norms or expectations prevailing on the continent.

Data as a public good would entail the creation of fresh, collective governance models, and an alternative set of concepts and values to sustain the new data imaginary emerging on the horizon. Innovations in bottom-up data institutions such as data pools, data commons, data exchanges, data unions, data trusts, or concepts such as ‘datasphere,’ ‘data as public good’ or ‘data as public infrastructure,’ are perfect examples.

Thus, I am proposing an alternative data imaginary, one that accounts not only for privacy and data protection but for all data communities in the African data ecosystem developed under African people’s values. I am certain that this would ensure the availability of data for business innovations, government services, and the production of goods or services to maximize data for the public good. This logic demands a system design approach by African politicians to not simply adopt model laws based on the GDPR, but also understand the need to develop norms that clearly – while respecting privacy – set data as a public good within the African value system pointed out above.

Way Forward

Big Data can no longer continue as a single ‘accepted way of interrogating the world and synthesizing knowledge’ about data, its innovations, and people. Africa must consider new configurations of relations between subjects and information and knowledge, and how these articulate novel ways of knowing and new paradigms of governance.

An alternative context-based data imaginary, in which data is viewed as a public good belonging to the people, will help make more data available for business innovations and other developmental needs, to better the human condition. Such a data imaginary would look to the continent’s rich heritage of values and belief systems for inspiration in efforts to create fresh institutions for data governance, ‘The collective data imaginaries are the fuel from which more just datafied societies can emerge and thrive[!]’

In my next posts, I will explore the relations between governance and networks, as a way to emphasize an African values-based approach.

References

African Union (2014) ‘African union convention on cyber security and personal data protection’. The African Union.

African Union (2022) ‘AU Data Policy Framework’, pp. 1–84. Available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/42078-doc-AU-DATA-POLICY-FRAMEWORK-ENG1.pdf

Beer, D. (2017) ‘Envisioning the power of data analytics’, Information, Communication & Society, 21, pp. 1–15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1289232

Daigle, B. (2021) ‘Data Protection Laws in Africa : A Pan- African Survey and Noted Trends’, Journal of International Commerce and Economics, (February), pp. 1–27.

European Commission (2022) ‘REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data’, 0047.

Gray, J. (2020) ‘Data Worlds’, pp. 2018–2020.

Hintz, A. et al. (2022) Civic Participation in the Datafied Society : Towards Democratic Auditing ? Civic Participation in the Datafied Society : Towards Democratic Auditing ?

Karenga, M. (2017) Seven principles of Kwanzaa, Smithsonian. Available at: https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/ seven-principles-kwanzaa

Ndlovu, T. (2021) ‘Isiphala Senkosi to end Hunger in Mangwe’, Chrinicle, 14 September. Available at: https://www.chronicle.co.zw/isiphala-senkosi-to-end-hunger-in-mangwe/

Porciuncula, L. and Chapelle, B.D. La (2022) Hello Datasphere — Towards a systems approach to data governance, Dataspheare Initiative. Available at: https://www.thedatasphere.org/news/hello-datasphere-towards-a-systems-approach-to-data-governance/ (Accessed: 18 December 2022).

Ruppert, E. (2018) Sociotechnical Imaginaries of Different Data Futures An experiment in citizen data.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2022) ‘REGULATION (EU) 2022/2065 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market For Digital Services and amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act)’, Official Journal of the European Union, 2022(October), pp. 1–102.